Gabriel Byrne meets a woman walking her dog in the street. She is evidently someone he knows of old. She's very pleased to see him and asks, "So, you back now?"

Gabriel looks blankly at her, scratches his chin. You can hear fingernails on his his beard's stubble. "Back?"

"In New York?"

He's so sweet. Part of his brain is thinking, No missus - this is in fact a cunning holographic image of me. I'm actually in Florida right now, drinking a fruit-juice cocktail and wishing I knew how to swim in the hotel pool. Another part of him is wondering what kind of an auspicious moment is this, his first time back in the city for five months, and he can't understand a word anyone says to him. She sees his consternation and pats him encouragingly on the tummy, laughs, sets him back at his ease.

"My house got flooded. Again," he says lugubriously. She looks at him with an expression that suggests she would like to stroke his hair, pat his head, and make it all better. She settles for touching his stomach again. (Now, what is THAT all about?) The woman remains undauntedly optimistic, proclaiming the flood to be a wonderful opportunity for him to stay in a luxury hotel in the city. Gabriel looks faintly perplexed and she says "Isn't that what you wanted to do? A little bit? Right? No?"

"Maybe. Just a small little bit."

"See now, when you came home, you realised you wanted to come home. You have to watch that stuff now. You think you want something and it's taken away .. uh-oh!"

I myself have no idea what the dear woman is talking about but Gabriel laughs congenially, generously, with that sonorous chuckle of his that I love. She touches his belly again. It's beginning to bug me. "Well, you know," she says. "It's tough. It's tough to be you."

"Tough to be me?" More laughing, more patting of the belly. Who is this woman, a personal trainer or something? Gabriel turns his attention to the dog, which looks a bit like the one from Madigan Men. It licks his hand appreciatively. I imagine Gabriel remains unperturbed, even if he were to find his hand covered in slobber.

"Well, you know, keep in touch .." says the woman eventually. "We miss you!"

"Yeah," says Gabriel, sounding a little wary. "I miss that old torture chamber ..." Oh. I see! So she IS a personal trainer then. I bet she owns a ... ~shudder~ a Gymnasium. They kiss amicably and part.

The film starts properly with the dawn of a new day over Brooklyn, New York City. At that time of the day, even the graffiti looks attractive.

"I think I've always had a desire to move. To travel. I left home for the first time when I was eleven. Then I left again when I was twenty-two, to live in Spain. Then to London, then to New York and then Los Angeles. So in one way I've always been moving around."

Gabriel is walking through his neighbourhood. He's wearing black. He looks fantastic. The leaves on the plane trees that line the street are just beginning to turn, rifling in the backs of their closets and fishing out their Autumn clothes. It looks peaceful, gentle, a nice place to raise a family. The dying leaves are beautiful against the red and brown brick and the black wrought-iron work, of his house.

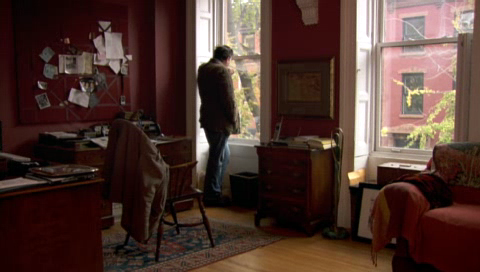

He shows us around the inside. It's a fairly typical Brooklyn house, or what I imagine such a place to be, anyway. One climbs the steps to go inside then has to go back downstairs to the dining room, the kitchen and the french windows to the back garden. Everything is in disarray. You see this gradually, as Gabriel slowly and methodically opens the wooden shuttering. The noise of his actions echoes. Light begins to spill into the room, in exactly the same was as the film itself begins to illuminate this fascinating man.

"This is the second flood that I've experienced." he says, unable to keep the frustration out of his voice. He walks on into his house. The floorboards creak ominously under his weight. It seems cold and dark, noises bouncing back harshly from hard surfaces. And empty. There's no furniture in the rooms he surveys, no paintings on the walls, no rugs on the parquet floors. Imagine, after months away filming, to come home to this desolation. But his mood lightens. You can hear him smiling as he talks about his son, Jack. "My son said to me, 'I think there's a Biblical curse on you, Dad. It's like God got up today and said, 'Things To Do: Put out trash. Sort out the Middle East. Flood Gabriel Byrne's house ...' "

Gabriel descends his stairs. One room is packed with cartons and boxes and pictures are stacked up against the furniture rail, for all the world as if he had just moved in yesterday. "But in fact it's something I can laugh about now," he says. "In a kind of and empty, bitter way." This is typical of Gabriel's wry sense of humour. I need to tell the reader that it's important not to take him too literally. Reading his words here is very different from hearing them. He stands for a moment and surveys his life in boxes. There is a big framed 1930s travel poster, all bright colours, saying "See Ireland First!" Not this one,

- but one like it. There's something else I suspect is a theatre poster, judging from its shape and size. I used to have many of these on my walls when I was younger. I spot a film poster from Dead Man.

"I suppose you could call it 'Post-Apocalyptic Nouveau Style'," Gabriel says speculatively, leaning against the central breakfast bar in his kitchen. It's a well-appointed space but looks hardly used. There are quarry stone tiles on the floor. A fantastic stainless steel range. I would saw off my left hand with a blunted steak knife to get a kitchen like this, but all there is are newspapers, brown paper take-out bags, newspaper and an old coffee cup. You can see his back yard behind him. A garden table and chairs, a folded-down sunshade. Mothballed, unused, waiting for the owner of the house to return.

You suddenly realise, Gabriel Byrne lives on his own.

"The minimalist, ravaged, pillaged look!" he says, waving his arms around expansively. He's playing the part of a New York realtor all of a sudden. "It's actually a very difficult and sophisticated look to pull off .." And after a moment he grins and snorts a little at his own joke. I melt into a small and decidedly unsophisticated puddle on the floor.

Next we have a shot of Gabriel dispelling the myth that he is a technophobe. There he is, reading and/or sending a complicated-looking text message. (Laura Linney had to teach him how to use Skype or some such when he was filming Jindabyne in Australia. He called it "that screen thing.") According to Richard E. Grant, Gabriel Byrne could bring a whole new meaning to the words 'all thumbs', but here he is, doing it. With his thumbs no less.

I feel almost proud of him. I can just imagine his children badgering him repeatedly to use technology to stay in touch. My own children did the exact same thing to their father.

"I didn't go to New York to become an actor," he says in voice-over. "I went to New York because my ex-wife was from there. I went there because I wanted to see more of her."

And see more of her, he did indeed. We see a photograph of Gabriel and his children. It's one of those kitchy, staged, faux-Victorian sepia things that was all the rage - at least in the UK - in the 1980s. Gabriel is dressed as The Sheriff, with a big gold star on his lapel. How fitting! His son has on a hat that is several sizes too big and a black ribbon tie. His little eyes are squeezed tightly closed. Gabriel's daughter, perched on his knee, has the toddler's typical expression when faced with something outlandish. "WHASSA, DADDA?" The picture is significant because it was my first really intimate view of him as husband and father, and not as actor. Millions of households all over the world have photographs just like this - imperfect. Eyes accidentally shut. Impatient, blurry outlines of small, wriggly children.

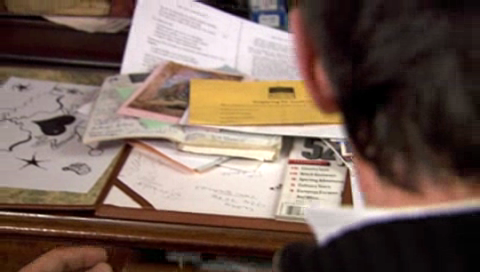

Gabriel Byrne: Hollywood Superstar? Nah, he's just an ordinary bloke. Who does ordinary-bloke things, at least sometimes. The photo is pinned, almost carelessly, on a big felt-covered noticeboard, the kind that is criss-crossed with ribbons, which hangs above Gabriel's desk. Next to it is a water-marked Polaroid of his family, including Ellen Barkin, and a coupon for a free newspaper. His furniture is all antique and a bit battered and none of it matches. I like that.

"But - as these things happen - somebody said, 'Oh, as you're here ... you might as well go and audition for that thing..' and I said, 'Oh, OK.' So I read the script and thought, this is a really interesting script and I went in and auditioned for it. Then I was ready to go home, and they offered me the part. And that was Miller's Crossing. It dictated a lot of what happened to my life, after that."

It's as if Gabriel has never really been master of his own destiny, not until relatively recently. I often perceive him as a man borne hither and yon on fate's unpredictable currents and rip tides. Just like the rest of us, really. We see some fascinating back-stage footage of Miller's Crossing being made. Gabriel almost jumps in too early, in front of the 'ACTION!' cue, which would have wrecked the shot. It's from the part where Tom barges into the ladies' bathroom and gets slapped about a bit by Verna, but he doesn't seem to mind too much. The camera focuses suddenly on actor John Polito, who is asking "I'd like to know his opinion, of what's it's like to work in America, this Irishman - " the camera pans to Gabriel. Again, that shy but expansive smile, the gentle laugh. My heart jumps about a bit. Does a little Irish jig in my chest.

Back to the present. Gabriel's desk top. Oh, God! The mess! He, or someone close to him, is a doodler. A sheet of paper next to his blotter is covered in big hearts and stars and long, flowing lines. It makes me think of his teen-aged daughter, or indeed of mine. "Let's see if there's anything else in here that's worth digging out," he says, sighing, and opening the big central drawer of the desk. Anyone who has one of these desks will recognise the mess in the Central Drawer. Directly underneath where you do most of your writing, the Central Drawer is always a repository of the most important - and the least significant - things that cross your desktop at any time. There is no really obvious sign of a computer. Anywhere. Or a typewriter. I wonder, does he do it all in long-hand? And give it to someone else to type up? Or does he have a laptop secreted somewhere about his person, just like his alter-ego Paul Weston? He yanks out a sheaf of papers nearly an inch thick. It's covered in neatly-typed names and addresses.

"Ah. Here's a good address book." How would he define a bad one, I wonder? He licks his thumb and leafs through it. Mick Jagger. Jeremy Irons. A quick impression of Jeremy Irons. Paul Newman. Charles Haughey. Gabriel pauses, looks up, into the middle distance. "I remember my mother saying, 'That man's on cortisone.'" Just the tiniest flex of his vocal chords, and Gabriel becomes a 50-year old woman. His own mother. "That man's on cortisone. That man's in a wheelchair."

Cut to the first in a series of home movies made by Gabriel and Ellen of their children. Their daughter, aged about two, runs to her grandmother. And now you hear the real Mrs. Ó Broin speak, and you know instantly where Gabriel gets his voice from, and you see her face, and know who he takes after. Her smile is identical to his. Juxtaposed against a back-drop of the everyday hustle and bustle of modern day New York, we hear Gabriel reading a passage from his autobiography, which begins, "It is early morning. Always I awake to hear my father downstairs." Fifty-five year-old images from Ireland butt up against 21st century New York. Surprisingly, it works. Because this is what Gabriel is - a man from 1950s suburban Dublin, with his Irish memories and language and thoughts and emotions, butting up neatly against what is arguably the most vibrant and multicultural city in the world.

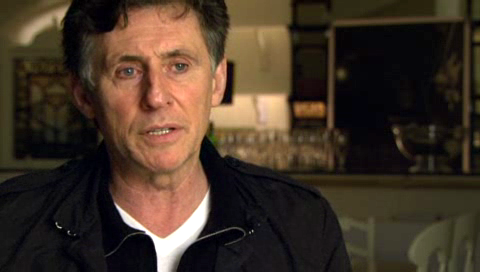

Now Gabriel is walking these vibrant streets. I get the sudden impression that he does this a lot (I have nothing to base that on, I admit. Just a feeling.) He is bundled up against the cold, and looks around him speculatively and yet with a certain reservation, almost nervousness. His stride is long for a man of his stature. He moves swiftly. Blink, and you miss him.

"I actually have a very good long-term memory, like a lot of people, and a very bad short term memory." (Not after filming two seasons of In Treatment you haven't, matey, I find myself thinking. ) "I register a lot of things during the course of a day and then if I don't keep a note of them, I instantly forget them." Gabriel is talking about his journal. His diary-keeping. He tries to define time. He tries to define the present. He talks about how transient it is.

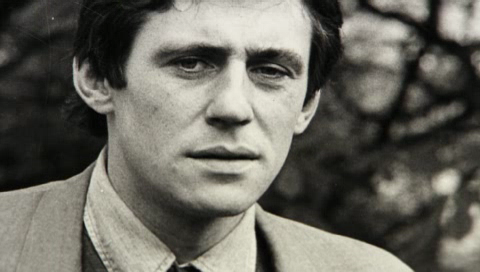

"Now is a peculiar .. it's gone! The idea that people will stop the present, and the past, and concentrate absolutely on THIS moment ... I don't know if that's possible. I think I try to do it though, by writing down what I feel at the end of the day. Even if its only two or three lines." Byrne is modest. "It's a vain effort to keep the present. And looking back over entries I made twenty years ago - I was reading one the other day - I find I am still preoccupied with the same stuff ..." We see and hear Gabriel in a very old interview, which I think may have been broadcast on RTE at the height of his fame in Bracken, where he reminisces about his childhood experience of going with his mother to fetch milk from the farm.

You can see and hear how, even as a young man, he was already sifting and sorting and cataloguing and re-visiting his memories. I bet you that even then, he already harboured ideas about putting it all into a book. He's very, very young. His hair is short, and his accent is long.

And - bang! - here he is again in the here-and-now, sitting on a park bench. He's watching the world go by, drinking coffee from a cardboard cup. I think of the John Lennon song, "Watching the Wheels" -

I'm just sitting here watching the wheels go round and round

I really love to watch them roll

No longer riding on the merry-go-round

I just had to let it go -

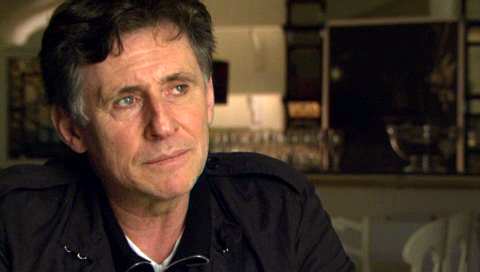

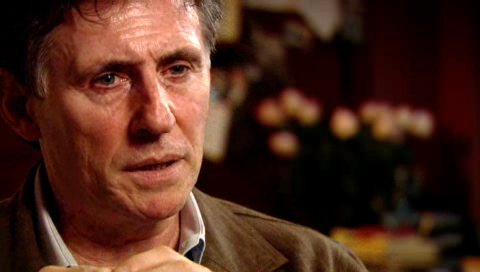

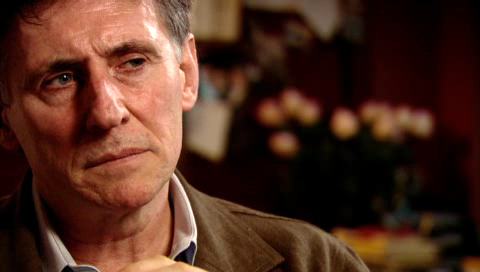

"I rarely think about tomorrow," says Gabriel suddenly. He drags me back into his film. "I'm more susceptible to the past than the future." Another home movie, this time from behind-the-scenes during the shooting of The Usual Suspects. Kevin Spacey does his impression of Al Pacino, through a mouthful of coleslaw, as a special present for Gabriel's sister Breda. Huge amounts of giggling. Gabriel looking extraordinarily handsome, even for him, in a blue shirt and with his hair all over the place. Voice-over again. "I went into acting primarily, banal as it sounds, to improve my social life." Back in Brooklyn (?) now. The film jumps all over the place like this, which looks untidy as I am recounting it here, but which works PERFECTLY when you see it on the screen. Gabriel is sat in a dining room, which is beginning to look like it is getting ready to receive people. A large number of matching wine-glasses are laid out on a sideboard behind him. Or, I've just realised this, it may not be his home. It could be a restaurant, or a bar. Gabriel used to own a restaurant in Manhattan, "Balitore", it was called. In Third Avenue. A million years ago. Oh, now I'm doing it. Swinging backwards and forwards in time, in Gabriel's life, in my own.

"Somebody said that you could be an amateur actor, and that you didn't have to be any good; that if you took some elocution lessons you could get into an amateur drama group. So I knew this guy who used to drink in one of the pubs, who everyone said 'spoke very well'. Which meant, actually, that he spoke through his nose, with a Dublin 4 accent - "

I think Gabriel is referring to a Dublin post code. See here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dublin_4

Gabriel imitates the accent. It's like someone with two pencils stuck up their nose. " - and he had a great way of talking. And I said to myself, if I could learn to talk like him, then maybe I could get into the theatre, so. He gave me a couple of lessons. I went down to this local drama group, the Dublin Shakespeare Society, because it sounded very grand. And that was the beginning of it. A very exciting time. Because I discovered that I was among people who felt like I did, and loved the theatre in the same way that I did. So when people would ask me, 'So, what are you up to?' I'd say things - very pretentiously - like, 'Well. We're on tour at the moment ...' which meant we'd all get into a big mini-van and go down to Enniscorthy for the night. And maybe eight or ten people would come out to see these things. You'd get the kind of applause that would be like a mixture of relief and derision at the end. And that was it. And then it was off to the pub."

He gives his wry smile. I think, Mighty Oaks, From Tiny Acorns Grow. Look at you now, man.

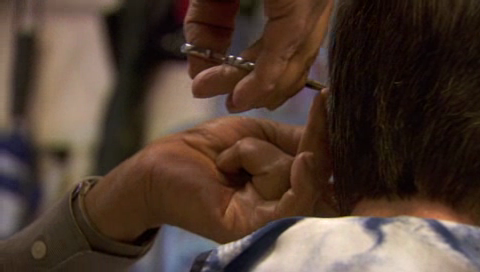

Now we're looking into Block's Drug Store, the storefront of which is a truly iconic image from the East Village. Gabriel is in there getting his hair trimmed by an affable Italian guy. Women in the shop, getting manicures, simper quietly in the background, throwing surreptitious glances over their shoulders at the smart fellow in the barber's chair. I hold my breath as the scissors set about Gabriel's locks. Sacrilege.

A handful of mousse gets worked into the mix somewhere along the line. Not the last and many more to come, no doubt. Hey! Why haven't L'Oreal snapped this fine-looking Irishman up for their advertising campaigns? I don't understand it. Oh. Oh. That's right. They went for PIERCE BROSNAN INSTEAD. Huh. Harrumph.

They pass the time of day. The barber likes Irish women. Gabriel tries to fathom why the man married and then divorced two of them. Which brings us neatly into the subject of Women In Gabriel's Life.

Áine. Áine. Back in the Seventies, reporting from the annual Jacob's Television award (Gabriel was honoured with this award in 1979 for his work on Bracken.) She is young, extremely beautiful, confident and well-spoken. "I met Áine in 1976. I was still a teacher at the time and she was working at RTE. She was a major television personality. I entered a new phase of my life when I met her. She turned up at my squalid apartment on the South Circular road with two poodles. At two o'clock in the morning. And a small little handbag. And that was it." Gabriel's voice is very quiet. There are longer pauses between his sentences. I feel the breath catching in my throat. "We actually lived together for ten years and she encouraged me and said, 'Look - you've a choice. You can go back to being a teacher, or you can try and do this full time.' "

The camera roams over some beautiful black and white framed photographs of Áine and Gabriel which are evidently on display in pride of place, somewhere in his house. It's a very intimate moment, and I feel uncomfortable. Áine O'Connor is dead. She died in 1998, two years after directing her old lover in an Irish-language film he wrote the screen play for, Draiocht. Against a backdrop of clips from The Riordans and Bracken, we hear Gabriel talking about how at that time there were only two television programmes that anyone in Ireland would watch - The Late Late Show and The Riordans, and it was Gabriel's first encounter with people crossing the line between reality and fiction, where people would say to him, in all seriousness - "You'd better look out! If they find out about you and that Maggie then you'll know ALL ABOOT IT!"

"They'd say things like that to you and you'd think they were joking. But .. they wouldn't be." Gabriel looks faintly shocked by this notion. Of people not quite knowing the difference between real life and television. Back in those days of course, with television in the UK and Ireland still in relative infancy, this is not so surprising. Nowadays, bizarrely, with the rise of so-called Reality TV, there ARE no differences between real life and television, a fact even Gabriel is not immune to. There is no sign of a television in any of the interior shots of his home, by the way. If someone were to tell me he doesn't HAVE a television, I should not be in the least surprised.

Gabriel crosses the Brooklyn Bridge. He looks like a man set up to walk all day long - he has his easy, rolling stride, capacious bag slung casually over his shoulders, ready to receive gifts of newspapers and secondhand books that he acquires on his travels. I bet he has a notebook and a couple of pens in there, too. The sunshine makes the worn metal of the bridge gleam a little, washing over the rust patches, as if it were made yesterday. People coming towards Gabriel spot the camera dogging on his heels and move seamlessly to one side without a second glance, as if a celebrity with a film crew midway on the Brooklyn Bridge is de rigeur, something they see every day. And indeed maybe it is.

"When I crossed the Brooklyn Bridge I thought: Ah, this is the New York that I've been looking for. This is the New York that I always thought existed, but which I could never quite find." Birdsong. Streets with no traffic. "It's a very still kind of area. You can hear the birds - " (he says 'boirds') "in the morning. That's not a sound that you associate with New York."

Gabriel sits on a park bench reading a paper, then walks along a sun-dappled street with bikes chained to rails and a woman pushing a pram. As he walks he is singing to himself. I refuse to believe his (and that of many of his fans) assertion that he cannot sing. Maybe he simply is not comfortable singing other people's songs, in front of other people. I'm telling you, his voice is sweet. "It's also where my kids go to school. I bought the house because I wanted to be near where my kids went to school. So when they got out of school they didn't have too far to travel." This brings a lump to my throat. Again. I'm starting to get used to it. "One of the really great things about being out here is that it's so quiet, that it feels like it's almost in the country." Gabriel is standing in his back yard, and you can hear him fingering his keys and the small change in his pocket. It really is so quiet.

"I do feel that in Ireland I am constantly colliding with the past. Whereas in New York, I have a kind of a clean slate. I'm free to compose my own present whereas in Dublin I am constantly being defined by my past. And that's nothing against Dublin, that's just the way. It's my relationship to that city." Gabriel walks again. Now, suddenly, he's in Dublin. It's after dark. You can hear the fabric of his trousers moving over his legs. He passes the Olympia Theatre. He's in Dame Street again. "In this place where I went to school, one day there came a man. All I can remember about his talk is he said 'hands up the boys who would like to be priests?' He had shown us pictures of Africa. Men with straw hats, riding on horses across rivers. Smiling black kids. I thought - that looks like a good job. I think I'll volunteer for that."

Gabriel could only have been - what - ten years old? The recklessness of the decision that was to impact upon his entire life is not lost on me, the mother of an intelligent, highly imaginative boy of that same age. I cannot imagine allowing my son make such a choice. It was based on pure fantasy, as were several of Gabriel's later choices. "I remember we had to go to this society, where they would help young priests. My mother had to go in and ask for help - financial help, 'cause the seminary I was going to was in England. And help was given. No problem." Gabriel takes a deep breath. "Because that was the thinking of the day. That to be a priest was to be in some way marked by ... by God. And so at the age of eleven I left Ireland on the mail boat. One December night, I remember."

Did he miss Christmas with his family that year, then? Again, I find this inconsolably sad, and hard to comprehend.

Gabriel's voice is partly laid over footage of him walking in a busy shopping area of Dublin. I notice him noticing a pretty, blonde woman. Of course I notice. He walks past brightly lit shop windows and you can hear a busker playing. But then you cut back to Gabriel in his kitchen. Dining room. Or maybe he is in a restaurant somewhere. He never seems to be still. The film's editing emphasises this. One moment he is walking, the next he is static, but not for very long. And the 'present' is just the filling in a sandwich made of the past. His story is like a temporal Oreo Cookie; a Jammie Dodger. "I had the distinction of coming back to Dublin at fifteen and a half years of age, being a failed priest. Nothing much was said, one way or another. I started working in an insurance office, as a messenger boy, making three pounds a week."

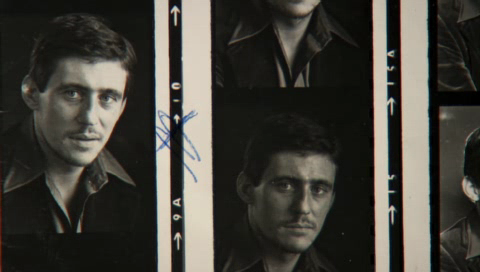

The viewer is treated - no, I'm not sure that is the word. 'Subjected', maybe - to a series of very early contact sheets of head shots that Gabriel must have had done when he was very first considering acting as a profession (head shots are not cheap, even now.) He looks awkward and very much less than comfortable in these ancient pictures. Young. Mustachioed. Concorde collars so typical of the 1970s sartorial disaster that was 'fashion'. But at least he did not have hip-length hair. One has to be grateful for small mercies, however tiny they might be. I wonder for a moment how many times Gabriel Byrne has been photographed since then, and my mind begins to collapse under the strain of trying to calculate it.

"I worked in a bar. I worked in a gay bar. One of the only gay bars in Dublin. I was an apprentice chef. Then I became a plumber. Probably the worst plumber in Dublin. I had a boiler suit and I used to go to work every morning with sandwiches ..." Another head shot. It stands out. This time he is wearing one of those brown leather and sheepskin flying jackets. He looks fed up, pensive - dare I say this? - broody. Half of his face is hidden in shadow. Ahh, I think. I recognise him now. Now THAT'S Gabriel Byrne. "And the I got a job in one of the hospitals in Dublin, in the morgue. It didn't last for very long." He laughs at the humour in his tone and the camera cuts.

This whole sequence is cut very fast, like a list, Gabriel reeling off a never-ending sequence of job after job after job. "I got a job repairing bicycles for a while, which I knew nothing about, either." He pauses for a moment and looks searchingly into the air. "Why I never found a job that I was any GOOD at, or that I had any kind of capacity for, I don't know." He sounds a little like the exasperated parent of an intelligent but rather aimless teenager.

And he asks this question in genuine ignorance. He doesn't seem to understand, even with the benefit of hindsight, that all the qualities he has now are the same he had then, and all of those qualities make him superbly qualified for being an actor. Does he not get that, then? I scratch my head in puzzlement, and start the film up again.

"I sold encyclopedias for a while." Gabriel tells the story of his friend Carl Daley, an encyclopedia salesman, who's stock-in-trade catch phrase was "You've gotta think positive!" It is in this kind of storytelling that Gabriel really excels. Every character he recalls and describes has his or her own voice. Their own intonation, and accent. "Myself and this guy from the North of Ireland tramped around all these suburbs of Dublin selling encyclopedias. In order to entice people into buying these encyclopedias - your spiel was, you had to say with as much sincerity as you could muster, 'You do realise how important education is for your children?' So you'd guilt them into saying, oh I don't want my child to grow up being an ignoramus. I'd better sign up for a hundred-and-forty four A-Z Encyclopedias of Knowledge." I notice he says "ay-to-zee" instead of "ay-to-zed". He's been in America a long time, after all. Gabriel looks like a naughty schoolboy at this point, thinking of his deception, the struggle to keep a straight face. It must have taken all of his fledgling skills as an actor to persuade people who really, really could not afford to do so, to invest in an expensive set of reference books. And especially so, given the absolute irony of his own situation at the time - uneducated, drifting, an academic failure. Going nowhere. He might as well have said, "Get these books for your little-ees missus, else they'll end up like me." Gabriel's roguishness didn't end there. "As an incentive then, you would say, 'Of course, you realise, you don't just get the Encyclopedia. You are also entitled to two years free supply of Tool and Spade or Field and Stream!' Magazines in which people in Clonshaugh or Killester had no interest whatsoever. So. I did that for a while. I began to see that that kind of picaresque lifestyle was getting me nowhere. I had a kind of Road to Damascus moment where I thought: I'd better go back to school..."